Rah! Rah! Rah!

Let's Cheerlead For ... the FCC!

Prometheus Defends the FCC in Court Against NAB Laws

When we mention the Federal Communications Commission, the names that come to some people's minds may not be words that you're allowed to say on the radio. Yet in December of 2007, the FCC actually took a step in the progressive direction to protect Low Power FM. They started granting temporary waivers for LPFM stations suffering encroachment from a Full-Power outlet to use another channel with a special waiver of the second adjacent interference criteria, the same way they allow repeater stations for big commercial stations. They also made a procedure where if a LPFM had no options for where to go even with the second adjacent exemption, the FCC might reject the full power stations application to take away the LPFM's channel. The National Association of Broadcasters got so mad about this that they filed a lawsuit against the FCC, because the FCC had agreed with low power groups.

For once, the FCC did the right thing, and now they're being sued for it. In response to the NAB's suit, Prometheus, represented by our fantastic lawyers at Media Access Project, has filed an intervenor brief supporting the FCC's actions to help secure Low-Power radio's place on the dial. To read our Petition, click here

A Little Bit of Background:

When a radio station applies to the Federal Communications Commission for a license, a few questions must be answered for the FCC before it can grant the request. The station must prove that it does not interfere on the first or second adjacent channels (for example, 91.3FM cannot exist if channels 91.5FM or 91.1FM, or 91.7 or 90.9 for that matter, are currently licensed to other parties). The FCC calls this the “Minimum Distance Spacing Methodology,” we call it “ the spacing rules” for short. In 2000, Congress took the unusual step of imposing a law onto the FCC regulatory process over technical matters (ordinarily Congress leaves engineering to the engineers who work at the FCC, since most Congresspeople are not radio engineers and would not know a dBu from a door knob)! The National Association of Broadcasters lobbied Congress and as a result the legislative branch heightened restrictions to include 3rd adjacent channels; although a later study by the MITRE Corporation proved that interference on the 3rd adjacent channels is negligible. This decision further limited the options for LPFMs on the band.

Because Congressional laws carry more weight than an FCC rule or regulation (the structure of the FCC as a Commission is such that it functions beneath the legislative body), they had to comply with Congress' decision. However, within the limits imposed by the law, the Federal Communications Commission took measures to protect LPFMs in December of 2007 with the release of their Third Report and Order and Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Creation of Low-Power Radio Service (section 73A-75) ( we'll just call this the 3RO&2FNPRM for short, OK)?

It basically gives LPFMsoptions for relocation that fall outside of the established "Spacing Rules". It also goes one step further and provides a possibility for the Full Power station's move to be denied if the LPFM is shown to provide a greater public service than the full power station. If the NAB is successful in their current lawsuit against the FCC, these protections for LPFMs will disappear in favor of the old process for dealing with encroachment; in short, if a Full-Power station wants your spot, they get it. Your LPFM station is dead, unless you can find a spot somewhere else on the dial using all the regular spacing rules. This 'simple' system says that LPFMs have no rights to the airwaves.

So Why the Waiver?

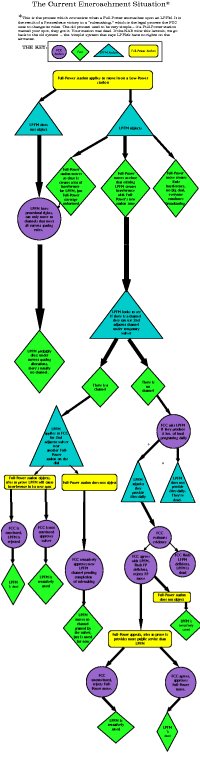

Full-Power stations in small towns often like to move their transmitters close to bigger cities (more people = more money for them). This is called a change of Community of License. When a Full-Power station wants to move, they have priority over the desired space, even if there's an existing LPFM operating on that channel. With their December 2007 decision, the FCC now allows LPFMs to move to another spot on the dial in these displacement cases, because sometimes there are open places that aren't available under normal spacing rules. The LPFM in distress can apply for a temporary, waiver to broadcast on a 2nd adjacent channel when there is no other alternative. Though the station must still go through the complicated and annoying steps involved in displacement – to first accurately communicate the change to their listener base and move their resources, studio space and equipment – they can at least stay on the air.

And Then, The Final Chance...

If there's no channel available, even under these new waiver rules, the LPFM has one more shot. The FCC imposes its “8 hour” litmus test. If the Low-Power station cannot submit that it provides 8 hours of local programming each day, they'll be forced to close their doors. If the station demonstrates that they do provide these 8 hours, the burden of proof shifts to the Full-Power station, who must exhibit their work in service of the public. The FCC then goes over the evidence and multiple outcomes are possible. They can side with the LPFM and reject the Full-Power's move. The Full-Power might (emphasis on the might) accept this decision, and the LPFM stays on the air using the 2nd adjacent channel provided by the waiver. On the other and far more likely hand, the Full-Power can appeal the FCC's decision and try to say that it does more for the public good than the LPFM. The FCC must weigh the evidence again. If the Full-Power station convinces the FCC of their worth. The FCC then supports the Full-Power move, in which case the LPFM is, unfortunately, out of options for redress and must shut down. However, the FCC can side with the Low-Power station. In this case, the Full-Power move is rejected and another station is saved.

Whew! For some visual aid that breaks down the decision flow, click here.

A Pat on the Back for the FCC:

In granting these temporary waivers, the FCC now has "taken modest steps in protecting local communities from losing their local outlets for expression" (MM Docket No. 99-25, filed by Prometheus et al April 7 2008). They did not make final rules, and asked questions of the public about what those rules should be. They offer tentative policy in the public interest, not standard practice, like "Would modifications to these policies better balance the interest of LPFM and full-service stations?...Should the Rules provide a deadline for the filing of the LPFM alternative channel application...? (FCC, Third R&O, sec. 73A, Dec.2007).

The National Association of Broadcasters is attempting to prove that the FCC broke the law and tried to circumvent Congress when they acted in favor of LPFMs by allowing these waivers. In fact, we argue that the FCC acted within its own structural mandate and within Congress' direction. First, the FCC has not come to any finalizing policy changes on this decision; they have only granted temporary waivers to stations being encroached upon while the policy is being debated. Second, Congress did not specifically ban action regarding the 2nd adjacent channel, only on the 3rd. Third, the steps taken by the FCC are not random, but in direct response to the adoption of "a streamlined procedure for change in community of license applications" (NAB v. FCC, On Petition for Review of an Order of the Federal Communications Commission, Brief for Intervenor, The Prometheus Radio Project).

Why do you need to know?

Since the case is in the District of Columbia circuit court, the issue is particularly tricky. There's 30-year (and counting) culture of deregulation permeating Washington, basically since the Reagan administration took office in 1981. Part of the economic policy from that time saw government oversight as interfering with market. The environment of this particular court is often hostile to public interest because of the legal environment down there: it's got a policy of unwritten policy of non-interference in public programs, except of course when it comes to favoring corporations or huge financial institutions.

Industry advocates of relaxed media ownership like the NAB are well-organized and well-funded in the Washington, D.C. area to appeal to the Federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit). Media conglomerates have been taking the FCC to task for decades, specifically within the D.C. Circuit, using all kinds of rhetoric, saying it has failed to prove that ownership limits remain necessary to promote the goals of diversity and civic engagement. The D.C. Circuit is the court system that eliminated the long-standing prohibitions which perpetuated this environment of hostility toward public interest in media, like allowing companies to own lots of different outlets (radio, newspaper, television) within the same market. For more of a history of this messy deregulated environment, click here. In spite of all this, we think we will probably win the lawsuit because the NAB's legal arguments have little real merit.

It's important to keep these tendencies in mind because if the trends of the D.C. Circuit prevail (if the NAB wins and LPFM stations can no longer use the waiver option), encroachment could get even more dangerous for low-power stations. Those stations who have received waivers could see those waivers thrown out. The FCC could adopt harsher policies into final rules. An environment already difficult for low-power to navigate could become even more treacherous. At this point, the FCC is acting only to promote and protect diversity and public service on the airwaves, a tenet of the organization's assignment. As ironic as it may seem given our history with the FCC, the Prometheus Radio Project will spend time in court this year defending the FCC as they preserve LPFM's opportunity to keep up their work of providing a multitude and variety of voices on the airwaves.

What can you do?

Most of the arguments in the lawsuit say that the FCC defied the Radio Broadcasting Preservation Act, the anti-LPFM legislation from 2000. The Local Community Radio Act is basically a repeal of that dumb bill. So if the bill is repealed, it takes all the wind out of the sails of the NAB lawsuit and the questions they raise become moot, moot, moot! Also, support of the Local Community Radio Act prevents LPFMs across the country from needlessly being shut down by opening up more channels for waiver options.

To read the NAB's intial brief, click here

To read Prometheus' brief, click here

To read the NAB's subsequent reply brief to the FCC, click here

To read the NAB's letter to all the lawyers, click here

To read Prometheus' Motion to Suspend Briefing Schedule and Hold in Abbeyance, click here

To read our press release NAB sues FCC on low power radio displacement click here

To read the Update from the oral arguments on the NAB encroachment lawsuit click here.